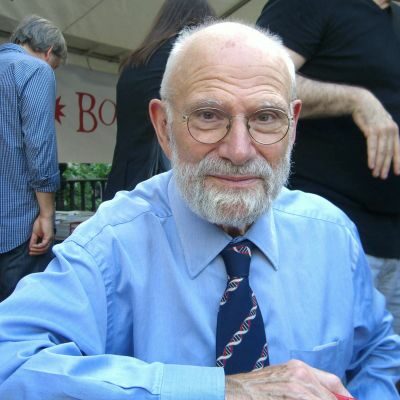

Oliver Sacks – Biography

Page Contents

Oliver Sacks, a neurologist, and the author has penned several books on individuals with frequently strange diseases. Awakenings and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat are a couple of his works.

Oliver Sacks- Birth, Education

On July 9, 1933, Oliver Wolf Sacks was born in London, England. He attended Queens College in Oxford to study physiology and medicine. Later, he pursued a career as a professor at Albert Einstein College of Medicine after studying neurology. Sacks published a great deal of writing regarding his patients’ pathological states.

Awakenings, Seeing Voices, and The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat are some of his works. At the age of 82, Sacks passed away from cancer on August 30, 2015.

Oliver Sacks, who was born into a family of doctors, was the youngest of four talented kids. His mother Muriel was one of the first female surgeons in England, while his father Samuel was a medical practitioner. Sacks spent his early years at home, but when World War II broke out in 1939, his family transferred him to boarding school at the age of 6 to keep him safe from the frequent bombing attacks that afflicted London.

Four years later, Sacks came home and attended the local grammar and high schools. He became interested in science and medicine and occasionally helped his mother with dissections while she was conducting research.

Sacks demonstrated a sharp intellect and excelled in school, just like his older siblings before him. As a result, he was awarded a scholarship to Queen’s College at Oxford University, where he enrolled in 1951.

Sacks graduated with a bachelor’s degree in biology and physiology in 1954. He graduated from the university in 1958, and following his internship at a hospital in London, he temporarily worked as a surgeon in Birmingham.

Oliver Sacks- Professional Career

Sacks traveled to Canada in 1960, and while there, he sent his parents a telegram advising them of his choice to remain in North America. Sacks traveled south by hitchhiking and finally arrived in San Francisco, where he immersed himself in the atmosphere, experimented with drugs, and made friends with several of the poets who lived there.

Despite these carefree excursions, Sacks stayed dedicated to research and attained an internship at Mt. Zion Hospital before completing a neurology residency at UCLA. Sacks’ professional journey brought him to New York City in 1965, when he started working at many local clinics and taught at the Albert Einstein College of Medicine in the Bronx. His first attempt at writing was inspired by the events of this period.

Sacks discovered a publisher for his book Migraine in the late 1960s. It included case studies of patients he had worked with at the clinic where he was still employed as well as his personal history as a migraine sufferer. Faber published Migraine in 1970 despite the clinic’s protests and attempts to prevent its dissemination, and Sacks was immediately let go.

The book would establish a formula that Sacks would use in the majority of his future writing, combining clinical observation, the storytelling prowess of a novelist or poet, and a deeply personal, human empathy rarely found in medical writing, even though it was only marginally successful at the time.

Sacks started as a consulting neurologist at Beth Abraham Hospital about the same time he started as a professor at Albert Einstein College. There, he met an extraordinary group of patients who were immobile, silent, and hanging in midair. Sacks identified their illness as encephalitis lethargica, sometimes known as the “sleepy sickness,” which had been an epidemic over the world from 1916 to 1927.

Sacks were able to revive the patients and treat their symptoms by administering the L-DOPA, which was an experimental medication at the time. However, the patients’ recovery was only transitory, as they either quickly reverted to their pre-treatment status or acquired new, comparable immobilizing disorders.

On May 18, 2019, American actor Miles Teller smiles for the camera during a photocall for the movie “Too Old To Die, Young – North of Hollywood, West of Hell” at the 72nd Cannes Film Festival in Cannes, southern France.

WASHINGTON, DC – MARCH 02: On March 2, 2011, in Washington, DC, ranking member U.S. Rep. Barney Frank (D-MA) interrogates U.S. Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke during his testimony at a hearing of the House Financial Services Committee in the Rayburn House Office Building on Capitol Hill on receiving “the Monetary Policy Report to the Congress required under the Humphrey-Hawkins Act.”

On October 2, 2010, in New York City, actor Ben Whishaw attended the premiere of “The Tempest” as part of the 48th New York Film Festival.

Sacks wrote a book named Awakenings about these encounters and released it in 1973. The play A Kind of Alaska, created by Nobel Prize-winning playwright Harold Pinter in 1982, was influenced by the book, which also served as the basis for a medical documentary the following year.

The book served as the inspiration for the 1990 critically acclaimed movie of the same name, starring Robert De Niro as one of the patients and Robin Williams as Oliver Sacks. Three Academy Award nominations were given to the movie, including Best Picture.

The Medical Poet Laureate

Sacks continued to lead his “double life” as a scientist and novelist, describing his rare medical experiences with a philosophical perspective and frequently poetic flare. He was once referred to as the “poet laureate of medicine” by The New York Times. The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, which Sacks himself suffered from, was published in 1985.

It contained previously published writings on diseases such as Tourette’s syndrome, autism, phantom limb syndrome, and face blindness. The Man Who Mistook His Wife for a Hat, one of his most well-known and possibly most illustrative pieces, was translated into more than 20 languages.

An Anthropologist on Mars (1995), tells the story of seven patients who have learned to adapt to their disabilities, and Musicophilia (2007), in which he discusses cases involving neurological disorders with a musical component, are some of Sacks’ other notable works.

In Seeing Voices (1989), he described sign language and its role in the culture of the deaf. Sacks published the autobiographical books Uncle Tungsten: Memories of a Chemical Boyhood (2001) and Oaxaca Journal on a more private basis (2002).

A Special Person

Sacks departed Beth Abraham Hospital in 2007 to take a job as a professor of neurology and psychiatry at Columbia University Medical Center. By giving Sacks the new title of Columbia Artist, which recognized the accomplishments that crossed the boundaries of art and science and permitted him to teach in a variety of areas, the university further demonstrated how highly it regarded him.

Sacks gained a great deal of recognition for his work as a teacher and author, including honorary fellowships from the American Academy of Arts and Letters and the American Academy of Arts and Sciences, as well as honorary degrees from Georgetown, Tufts, and Oxford. He attained the rank of Commander of the Order of the British Empire in 2008.

Sacks released a book titled The Mind’s Eye in 2010. He covered a variety of sensory abnormalities in it, as well as how individuals dealt with them. He also talked about his struggles with vision loss as a result of 2005 treatment for a rare kind of ocular cancer. In February 2015, Sacks exposed his life once more when The New York Times published an editorial in which the doctor stated that he had terminal liver cancer linked to his past eye malignancy.

Sacks said in a passage on accepting mortality: “When people die, they cannot be replaced. They create voids that cannot be filled since every human being is born with the genetic and neuronal predisposition to be an individual, to choose his path through life, and to meet his death. The foundation of Sacks’ writing on diseases and disabilities is this conviction.

In April 2015, Sacks’ autobiography On the Move was released. While Sacks’ deadly cancer was in its latter stages, he kept writing. In a narrative piece titled “And now, weak, short of breath, my once-firm muscles melted away by cancer, I find my thoughts, increasingly, not on the supernatural or spiritual, but on what is meant by living a good and worthwhile life — achieving a sense of peace within oneself,”.

he wrote in his article “Sabbath,” which was published in The New York Times on August 10. My mind keeps wandering to the Sabbath, the day of rest, the seventh day of the week, and possibly the seventh day of one’s life as well. On the Sabbath, one can feel as though their labor is over and can rest in peace.”

Sacks passed away on August 30, 2015, at his home in New York City. He was 82.